STANLEY ELKIN: JOY RIDE

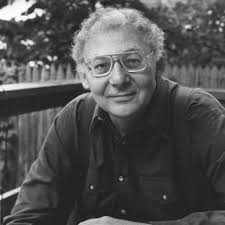

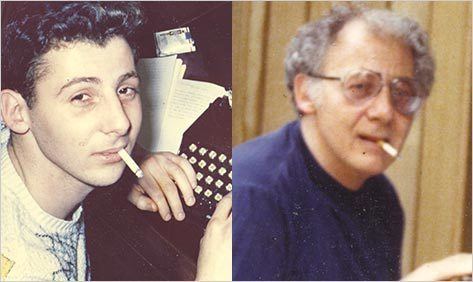

Stanley Elkin called me a prick. I was in the back row of a packed classroom at the University of Iowa. On the first day of class, Mr. Elkin walked in limping and sat down behind the front desk. He was uncomfortable in the chair. He introduced himself and then said, “I joined the Army when I was much older than your usual recruit.” He eyeballed the class. Long pause.

I had seen him read his fiction so I knew he was a tremendous performer. I thought, Uh-oh, we’re about to get blasted.

He said, “It was the biggest mistake of my life." He described his boot camp training to us. He waved his hands as he acted out trying to reason with a screaming drill instructor. The laughter started.

He described being surrounded in the barracks by the young soldiers who called him “Pops,” accused him of slacking on the obstacle course, and who blamed him for their lost privileges. He explained to them it was the Army’s fault. He was physically threatened and he shrugged it off, showing how he did it by jerking his shoulders down and turning both hands palms up. This, of course, only infuriated his attacker.

At this point, laughter ricocheted echoed down the halls of the English and Philosophy building. Then Mr. Elkin lowered his voice and described his isolation. His despair. Why had he done this to himself? What was wrong with him? The classroom went silent.

He told of setting out on a long hike, a twelve-hour march with a heavy pack that he never successfully completed before, but that he now must complete in order to get out of boot camp. He is last in a long line of soldiers. Soon there is no one near him. He is collapsing. He staggers to the top of a hill, half-dead, near the finish, and sees all the young soldiers -- it seems like hundreds of them -- sitting around waiting for him. He is sure they will curse him, but instead, they stand and applaud. He is not sure if there is mockery in the applause, but no matter, the welcome is such a surprise he savors it.

Mr. Elkin looked down as if in sorrow, held the pose. Then straightened up, smiling, eyebrows high. He had boxed our ears with a story.

I liked his short stories, but understanding what he was doing in his longer fiction did not come naturally to me. I grew up on the street poetry and short fiction of San Francisco and the down culture of Stockton. I favored sparse dialogue and the short line. My favorite literary novel at the time was Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays. Elkin’s dense rolling prose and the momentum in his novels and long stories could overwhelm me.

I am Spanish Basque and Irish from a working-class and farming background. My girlfriend at the time was Jewish and I often stayed at her family home in San Rafael where I grilled her English professor father about fiction writing. We were three weeks into the semester and discussing one of Mr. Elkin’s longer stories in class. I raised my hand and asked why in the story he had made the gatekeeper to hell Jewish. I was thinking Dante. Joyce. This was the kind of question that Mr. Elkin had asked us about other stories. But this time, Mr. Elkin stared at me in dead silence for a long time.

No one in the class moved. He said, “You are a prick.” Class dismissed. In the hallway, fellow students circled me. Some are outraged. One wants to snitch to the administration, but I made him promise not to do it. At this time in my life, I am living in a trailer park and supporting myself working as a bartender at Joe’s Place downtown where I am regularly called other names. Besides, as a daily drinker with the trashed life that follows addiction, I felt Mr. Elkin’s declaration was true enough.

A week later, the next scheduled class began and Mr. Elkin asked the class a question about the assignment. I raised my hand. I honestly had a question, but then I remembered what he had called me the week before. Everyone else in class put their hands down and waited. I wanted to put my hand down, but it was too late. Mr. Elkin, with one cocked eye, called on me. I said, “Well, sir, speaking from a prick’s point of view…”

I never got to finish the sentence. The class howled. Stanley beamed. We landed safely.

Stanley and I developed a certain bond. We never had the time or opportunity to become real friends. We moved in much different circles, but when we did connect outside of the classroom, it was always a story.

Stanley was great in the classroom and when mentoring writers he was direct and generous. Outside of the classroom, he could get jumpy. Agitated.

One night I ran into him at a party, an event he told me he was forced to attend. I was there for the free alcohol. We leaned against the back wall of a dining room overlooking a large room crowded with writers. He was not happy. The phone on the dining table rang. The host came into the room and picked up the receiver. There was that strange lull in the buzz of a room when a phone is answered.

Stanley looked at me. It seemed that he was daring me to react. I leaned toward the larger room and, as if I had answered the phone and was making an announcement, said, “Oh my God, your novel has been published!”

Heads turned and everyone in the room looked at our host. He kept talking into the phone, oblivious as to why everyone squinted at him. Stanley muttered, “Perfect, just right.”

I told him I stole the line from a John Hawkes novel and so we talked about Hawkes. He seemed happy for a while.

There were other encounters inside and outside the University. We never talked about each other’s writing, but he knew I was writing first-person short stories in voices other than my own and I think he liked that. When we did connect we often told each other stories. What had happened the night before. Anything that was fast and funny. His laugh was one of the best I’ve ever heard.

We talked about what made a story work and often talked about other writers and their writing. I want to make this clear: I loved him. The last time I saw him it was winter in Iowa. Snow falling. I was no longer one of his students. We ended up at the same party. There were some publishers there and most everyone was on their best behavior. We talked for a few moments and he was seriously upset about the weather. He ducked into the kitchen to get away from the crowd and after a few moments, the host of the party asked if I would take Stanley home. He said Stanley was having some kind of attack. I walked Stanley out of the house.

As we approached the street, we passed a circle of my drinking friends standing in the fresh snow, smoking. Without saying a word, they followed me to my car, a 1937 candy-apple red, four-door, hump-backed Chevy with a cave of a back seat.

Stanley was startled by the look of the car, but my friends surrounded him and eased him into the back seat, one on each side. A bottle was passed around. Stanley refused. Cigarettes are lit. Stanley coughs. We drive down the snowy street. Stanley says, “You guys are taking me home, aren’t you? This is the way to the Iowa House, right? I stay at the Iowa House. No, this is wrong. This isn’t the way. This is Mean Streets. This is bad. This car shouldn’t be out in the snow. Am I right about this? This is a dangerous car.”

Stanley is going crazy in the back seat. I’m driving twenty miles an hour through blowing snow. It’s hard to talk to Stanley when he gets like this: it’s part acting, part instigation, part challenge, part straight man, and definitely powered by honest anxiety. We laugh like kids laugh and Stanley laughs too, and then shakes it off and continues his worried rant. I try to assure Stanley that everything’s fine, but I can’t finish a sentence because he won’t stop talking and every line pushes us further. He says, “This is it, isn’t it? Your taking me for a ride. Where are we going? Oh, forget it. It doesn’t matter. I shouldn’t care. It’s over. What should I care? I don’t. Where are we going?”

It’s a long, slow, dizzy drive. I park in front of the Iowa House and one of the guys gets out and holds the door open. Stanley starts to get out and then hesitates. He asks, “Where’re you guys going? What comes after this? I’m home, right? I’m going in right here. This is the walkway, right here. What happens next?”

He doesn’t get out of the car. He can’t leave, he can’t stay. It’s like he wants to hang out more, keep going. He has this little smile on. He finally gets out and walks away from the car, thanking me many, many times for taking him home.

He walks with his shoulders forward, hunched-down, toward the lights of the Iowa House, looking back at us over his shoulder, at four kids standing around a ’37 Chevy passing a bottle. He stops at the door, turns back, and looks, not at us, but at his footprints in the snow.

(Book, music, & movie reviews; & interviews & fiction & mutual support & encouragement are all in play at dandomench.com - a forever free secure site with the highest standards of privacy available. Your free login is your email address and name - the only information the site retains. Your participation is not public. We never track you; or share or sell your email address. If you do choose to contribute, we never store that information. Add this website to your address book or drag the newsletter from your spam folder to your primary folder so we can stay in touch. You can contact me at dandomench@gmail.com. I will respond as quickly as possible. I am grateful for your friendship and support. Thank you!)